[FEATURE ARTICLE] New Straits Time: Finding hope – A mother’s touching tale about her two autistic children

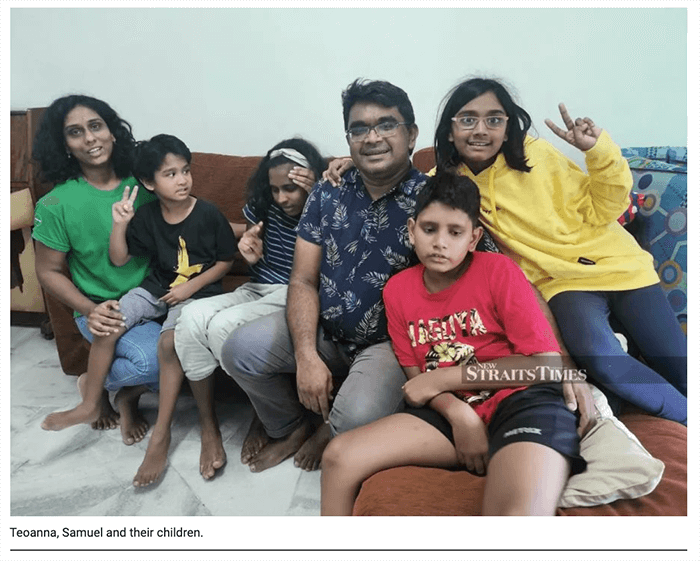

WHEN Teoanna James brought her children to greet me one fine day at my office two years ago, I was touched deeply. “My children and I just wanted to drop by and give you a hug!” she’d said over the phone. The smiling lanky woman with four children in tow greeted me at the lobby and gave me a tight hug.

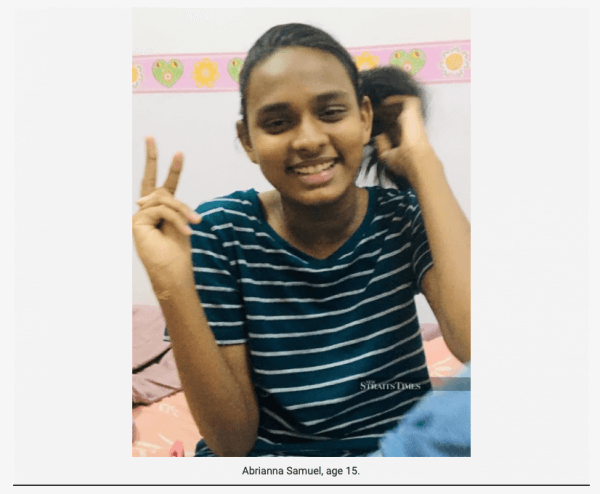

“Abrianna wants to give you something,” she told me, nodding at her eldest daughter who was clutching at her ears and looking at me with a slight frown. “Go ahead,” she urged her daughter gently. Gingerly removing her hands off her ears, the then-13-year-old snatched the rose off her mother’s pre-offered hand and gave it to me. “We love you, Aunty Elena,” chimed her second daughter Alyssa, smiling broadly. Her two sons said nothing, but giggled in delight as I reached and gave them all a hug.

My friend knew I was having a bad day and she came with children in tow, to cheer me up.

I’ve known Teoanna through a local gym that we’d both attended three years ago. I admired the sporty woman for her ability to fly through the workouts barely breaking a sweat while I huffed my way through the 45-minute sessions. Teoanna also worked part-time at the gym and I slowly grew accustomed to seeing her smiling face whenever I went for my classes.

Over time, I got to know that she was a mother of four, and as we got closer through the years, she let slip that two of her children were on the autistic spectrum. Eventually, I became aware that there were challenges when she finally had to give up her part-time job.

“I need to be at home with the kids,” Teoanna explained, eyes lined with worry. Her daughter, she told me, had been regressing and her son hadn’t been showing any improvements either. “It’s tough,” she confessed.

I never realised the challenges she must’ve been going through. I felt guilty because I’d never asked much about her family. I learnt that day that her eldest daughter was on the spectrum, high functioning but battling a severe anxiety disorder while her second son Aaryn was also diagnosed with autism but on the severe end of the spectrum where a high level of support was needed for him.

The word autism means different things to different people. To some, it conjures an image of the socially awkward eccentric who, besotted by a narrow set of interests, eschews small-talk and large gatherings in favour of solitude.

To others, it’s a profoundly life-limiting disorder that consumes every waking hour of a family’s life; a medical disability that entails unpredictable bouts of aggression resulting in torn upholstery, cracked skulls and savage bites.

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterised by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviours, speech and nonverbal communication. According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, autism affects an estimated 1one in 54 children in the United States today.

There isn’t any official registry for the number of individuals diagnosed with autism in Malaysia. However, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 1one in 160 children has ASD and its prevalence appears to be increasing globally. It’s estimated that around 1 one per cent of the world’s population is impacted by autism.

While the subject of autism is better known today than maybe years ago, it still remains a subject that poses more questions than answers. No two children with autism are alike. The term Autism Spectrum Disorder reflects that fact.

Even though each individual with autism has difficulties in the areas of communication, socialisation, and flexibility of thought, each has a unique combination of characteristics and so may seem quite different.

The ways in which people with autism learn, think and problem-solve can range from highly skilled to severely challenged. Some people with ASD may require significant support in their daily lives, while others may need less support and, in some cases, live entirely independently.

When I finally met her children that day in my office, it really hit me that Teoanna had her challenges cut out for her. Abrianna constantly clutched at her ears, her face drawn in discomfort while her 12-year-old brother could only articulate in sounds. Teoanna wasn’t fazed by the stares her family was eliciting. “I’m used to it now,” she confided with a shrug of her shoulders and a smile.

Over the next two years, we hardly met up. But I followed Teoanna avidly on social media where she documented her journey living with her family of five. “Abrianna was obviously cranky today”, she wrote one time. “Hitting/whacking me and continuously rubbing her eyes. She was under some form of stress. It wasn’t until I got home that I figured out the reason why. A quick Panadol and Abrianna was much better, dancing and singing again. I write this with much pain in my heart that I was SLOW to bring relief to my child. I hate autism. Wish everyday it could be me with autism and not my children. Everyday.”

The pain is real for parents with children on the Autism spectrum. Parents with autistic children go through insurmountable challenges daily. This host of challenges includes the inability of the children to fend for themselves, the child’s educational challenges and the stigma and stereotypes that come with having a child with ASD.

Stigma and stereotyping are very common issues for parents with children with autism.

The mere fact that parents have a child with that condition is a very hard thing to accept and the situation is made worse when society, instead of giving a helping hand, stigmatises you. The rate of autism in all regions of the world is high and the lack of understanding has a tremendous impact on the individuals, their families and communities.

Teoanna had another story to relate. One night, she and her children went on an unplanned trip to the local store. “Abrianna sometimes closes her eyes to regulate lights and sounds, which led her to accidentally knock down a child-sized mannequin,” she wrote. The mannequin fell on an adult man who managed to protect himself at the nick of time and save the mannequin from hitting the floor.

Outraged at Abrianna’s clumsiness, the man’s wife scolded her daughter severely.

“I turned in time to see the mannequin fall, the awesome catch by the man, his angry wife and my dancing autistic daughter,” she wrote, continuing: “I then looked at the wife and said ‘special child’. Her face showed no reaction and she walked away with her husband and toddler in hand.”

April 2 is World Autism Awareness Day, so designated by the United Nations, and started in 2008 to highlight the need to help improve the quality of life of children, adults and their families affected by autism.

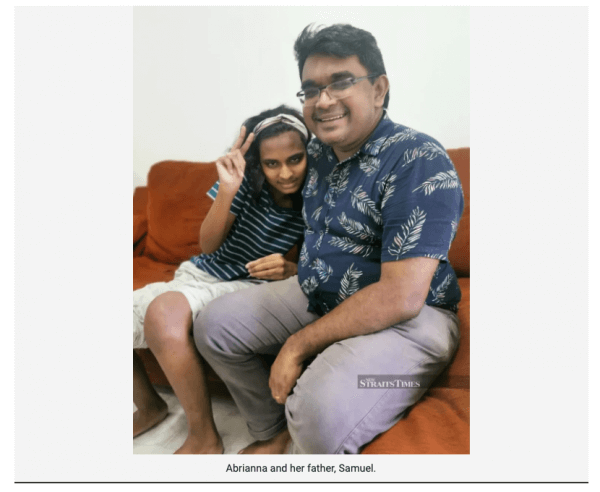

For every parent like Teoanna and her husband Samuel, who have children on the spectrum, the journey is often fraught with challenges, endless research, trials and errors as they constantly seek out ways to reach out to their child.

For a child with autism, the feeling of isolation can be overwhelming when one cannot communicate or understand one’s surroundings. It’s a journey that both parent and child take together to get past the murky isolated world that autism imposes.

DIFFICULT BEGINNINGS

“It’s been tough,” Teoanna admits over a recent Zoom call. With the pandemic hanging in the air, we’d agreed that it would be safer (for the sake of her children) to conduct our interview online. It’s around 9nine at night, and she looks tired. “The kids have gone to bed,” she says with a relieved sigh, before admitting that they could be quite a handful.

She gets straight to the subject. “I’m ready to talk,” she says vehemently. “I’m so grateful that you’re willing to write about this. If my journey could help someone else who’s facing the same challenges, I’d be very happy.”

Abrianna was born in 2006 and for the longest time, her symptoms went largely undetected. “I was a working parent back then,” she explains. She was a full-time graphic designer at a private hospital. “I really loved my job and was drawing a good salary at that time,” she recalls wistfully.

Both husband and wife worked, and Abrianna was sent to her in-laws’ place during the day. “My husband and I were typical young working parents at that time and we didn’t care to think or look out for her growth milestones,” she admits candidly. “You know how they say milestones are important? These days, parents are more cognisant of that and they keep track of their child’s milestones.”

They only picked up their daughter in the evening and had time for a quick cuddle before going to bed. “We only saw her at night, and the next day it was back to the routine of sending her to my in-laws again.” There were behavioural issues that showed up when she was still an infant. “She never cried at all,” recalls Teoanna.

As she grew older, she was still unable to verbalise her requests, could only focus on one thing at the time and wouldn’t respond when her name was called. But she was high-functioning, points out Teoanna, because she had mastered the basic concepts of cooperation and imitation. Abrianna had basic early learner skills where she could get by under the pretext of “oh my child is just shy!” or “my child is a slow learner.”

“We had plenty of excuses for her but it came to head when she was enrolled in kindergarten,” says Teoanna, adding simply with glistening eyes: “Our journey began then.” It finally hit the young mother when she arrived at the kindergarten to find her 4-year-old daughter clutching and bouncing off her teacher’s leg with grunting sounds amidst the stares of other parents and children milling around. “Look, your child has autism,” the teacher finally told Teoanna.

She didn’t know what “autism” was. “I refused to be educated,” she admits, adding: “Instead, I wanted to roll under a stone and just die. I couldn’t deal with it.”

A visit to the paediatrician confirmed the diagnosis. What’s worse, the doctor also diagnosed her son, born two years after Abrianna, to be on the autistic spectrum as well.

Just like Abrianna, Aaryn was a baby who never cried. “We didn’t know that Aaryn was autistic either. We just thought he was such a good baby who just drank his milk and slept at nights.”

The second blow was hard. “That’s when the depression sunk in,” she reveals softly. “For a while, my marriage was strained. Samuel (her husband) threw himself into his work while I went deeper into depression. I had three toddlers by then. Two were diagnosed with autism and my third child, Alyssa was also showing the same symptoms despite being normal. Because my older two were so quiet, she went quiet too.”

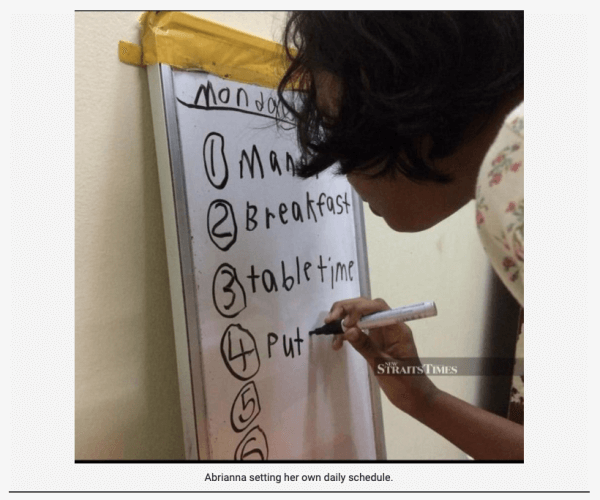

Things didn’t get any better. Abrianna was high-functioning but suffered anxiety attacks that led her to becoming violent. When you have children on the spectrum, says Teoanna, you’d have to explain to them exactly what their day was going to be like. “I didn’t know that then.”

She went to her local store to buy just one thing, and that trip became traumatic for both her son and her entire family. Aaryn couldn’t get a shopping trolley and he had a meltdown in public.

“He was on the floor, kicking me and screaming in full view of other shoppers. People were wondering why I didn’t correct my 6-year-old son. The security guards came running and wondering why I wasn’t doing anything to control Aaryn. Then just as suddenly, he caught sight of an empty trolley in the corner and the meltdown ended just like that. I realised that all he really wanted was a trolley and after that, he was fine.”

On another occasion, Teoanna was driving past the playground and Abrianna started pulling her hair and grabbing her by the neck. “I didn’t know that she wanted to go to the playground. She couldn’t vocalise it and started showing her frustration by grabbing me while I was driving!”

The daunting, never-enough demands of autism have remained inelastic, bottomless to both Teoanna and her husband. Not knowing what really works or helps make identifying the inessentials all but impossible. “You try everything and nothing seems to help,” she says softly, wiping a tear.

HEAVEN-SENT HELP

“I felt like I failed as a mother,” confesses Teoanna, her voice shaky. “I didn’t know how to communicate with them and I didn’t understand them.” What’s worse, she had another child who needed her love and care, but Teoanna was so focussed on caring for the older two who demanded her attention and time. “… and the older two were driving me nuts!” she exclaims.

She’d reached the end of her tether. No kindergarten would accept Aaryn because he couldn’t sit still long enough in class. “We kept trying to push Abrianna into the normal school system. That was a huge mistake.”

To compound it further, she’d already stopped working and finances were tight. “Living on a single income with children who need constant supervision and help can be draining,” she admits, adding: “They needed help and I desperately needed to find the help.”

And help came, she says firmly — from God. “I broke down in church one day and the first person to pray for me happened to be Jochebed Isaacs, the director of Early Autism Project (EAP), a pioneer of the provision of Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA) treatment in Malaysia.”

Applied behavioural analysis (ABA) is a type of therapy that can improve social, communication, and learning skills through positive reinforcement. Many experts consider ABA to be the gold-standard treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or other developmental conditions. The therapy broke down every quotidian action into tiny, learnable steps, acquired through memorisation and endless repetition.

“Children with autism resort to bad behaviour in order to communicate. What you need to do is to direct their energy to positive behaviour, using language. They have the capacity to use language but they need guidance,” explains Teoanna.

EAP offered scholarships for both her children, and in the months that followed, Teoanna and her family spent hours with therapists sharing their fears and frustrations, and swapping treatment ideas, comforted to be going through each step with someone experienced. Her children, especially Abrianna, progressed. By then, Teoanna had her youngest son, Aephraim.

“When my older two were younger,” Teoanna recalls, “I remember only darkness, only fear. I was like a zombie doing everything I could to help them except to love them. EAP helped shine a light into that dark abyss.”

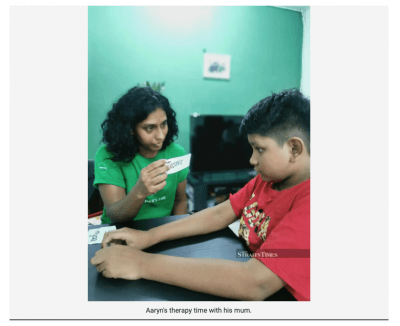

Without question, parents play an essential role in the ABA process. While a therapist is responsible for teaching new skills, a child with autism only visits with their therapist for a small portion of their daily lives. Alternatively, these children spend many hours with their parents, when their new behaviours and skills need to be reinforced and supported.

“As a mum, you learn the ABA techniques and become the ‘therapist’ at home. This is the best part of the EAP programme. The mum steps in as a therapist and you learn to do this with your child. That way, the quality of life at home increases,” she shares. “I’m living proof that a mum can take on the role as a therapist and run it at her home.”

Thanks to the techniques, the family celebrates every small milestone achieved by the children. “It’s a basically a reward system that encourages the child to behave and respond in the right way. And giving them that sense of accomplishment and empowering them to determine their own schedules,” she explains.

It was a huge relief. Soon Abrianna began to use language to communicate, albeit inventively at first. But there were hiccups. One time when Abrianna had a meltdown when her youngest son didn’t go to school, Teoanna was baffled. What had she misunderstood? Why were her tantrums so frustratingly arbitrary?

Suddenly, Abrianna exclaimed: “Amma, Ephraim go to school! Ephraim go to school!” It hit her: Abrianna watches everyone else’s schedules too. So if anyone in the family had a change in their routine, it has to be noted in her eldest daughter’s schedule or it would set her off too.

Adds Teoanna adds: “It was like, ‘Oh, my god, how many times have I thought her tantrums were random when they weren’t random at all?’ I felt so bad for her. What other things had she wanted to tell me but couldn’t?”

The journey is still fraught with obstacles, but Teoanna has found a way to reach out to both Abrianna and Aaryn, as well as her younger two children who aren’t on the spectrum. “I’m a better mum now,” she confesses, wistfully. “In fact, my younger daughter recently told me that I’m a much better mother these days because I have time for her.”

Adds Teoanna adds: “I learnt that I need to love all my children in the present. Not just pray for their future. Be present right here and now and love them unconditionally.”

She’s clearly unafraid to be candid. “I want parents with autistic children to know they’re not alone. I know the drill and understand the pain. We have to work even harder to ensure that our children learn all they can to reach their potential,” says Teoanna, smiling gently.

Adding, she concludes: “Families like ours need to open up about the reality of our lives if we’re ever going to get the sort of support we need and if the world is ever going to make a place for our children — while they’re still children and when they become adults.”

To learn about Early Autism Project Malaysia, go to www.autismmalaysia.com.